Jeena Wada Khilafi Hai

By Ghazi Salahuddin

Aaj Publications

ISBN: 978-969-648-128-7

194pp.

Stories are ubiquitous and take on many forms. Even the stories themselves have their own accounts — detailing how they came to be, sometimes shared in an instant and, in other instances, forgotten only to be revived later. Occasionally, the story of stories proves to be more captivating than the stories themselves.

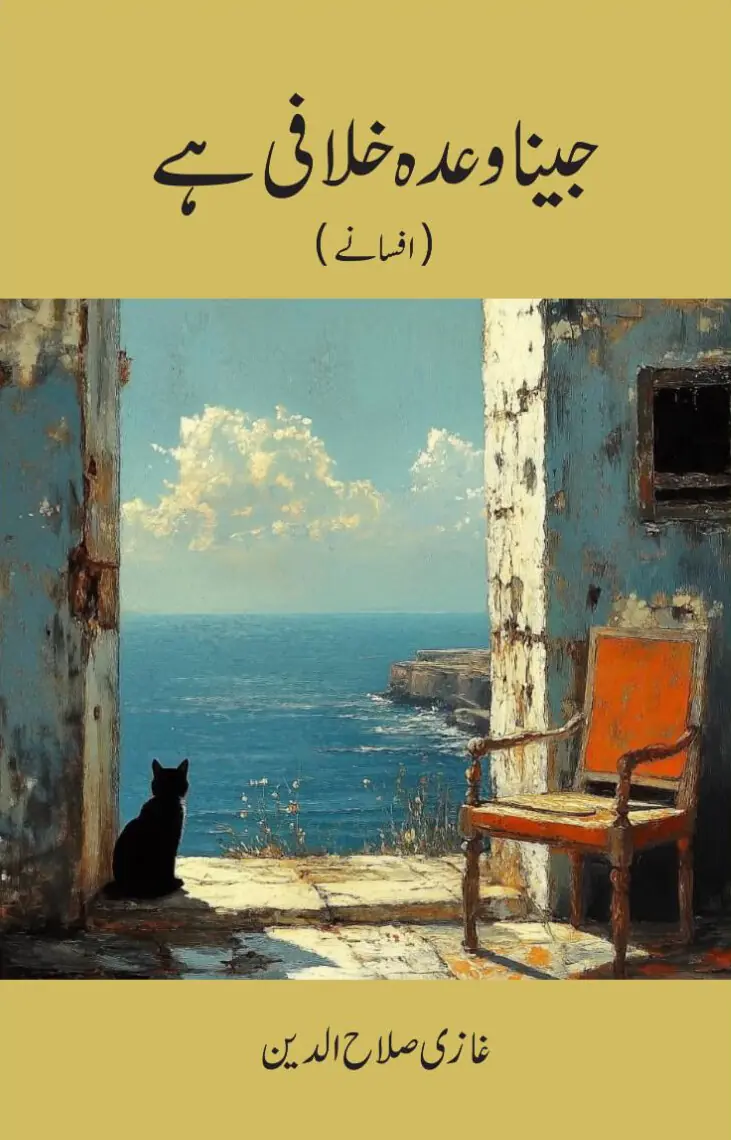

Ghazi Salahaddin, a distinguished journalist and social activist, has recently released his first collection of Urdu short stories, titled Jeena Wada Khilafi Hai [Living is Against the Pledge]. The story behind this book is just as intriguing as the 10 stories it contains.

These stories were penned in the 1950s, nearly 70 years ago, and were featured in esteemed literary magazines such as Adab-i-Lateef [Light Literature] and Naya Daur [New Era]. However, the stories faded into obscurity, even forgotten by the author himself. He ceased writing stories. Why? Ghazi sahib addresses this question in the book’s preface.

He reminisces that these stories received praise from editors and peers, but he needed to learn English for his journalism career. He is entirely self-taught when it comes to his command of English. He acquired the language not through formal education, but by utilising the resources of the British Council library in Karachi. He proudly claims that, for him, this library is his equivalent of Harvard and Oxford.

A collection of long-forgotten short stories by journalist Ghazi Salahuddin resurfaces in the form of a book, leading to the question of whether these tales of young angst about love and belonging still resonate

Did he forsake Urdu, his mother tongue and national language, in favour of English, the colonial global language? The reality is that he did not forsake Urdu; he continued to write Urdu columns and, particularly, essays about his travels in Jang, which were later compiled into Meray Sahil, Meray Darya [My Shores, My Rivers]. However, he never returned to fiction writing. His departure from fiction was complete. Nevertheless, he has remained an enthusiastic reader of both English and Urdu fiction all along.

His departure from writing fiction seems more related to writer’s block than merely his pursuit of a journalism career. Writer’s block can manifest in various forms and durations; some instances are fleeting, while others can be enduring. In every case, writer’s block stems from a deep shift in the writer’s mindscape. Simply put, the causes lie within, not outside.

We can infer that Ghazi sahib explored what he needed to through his Urdu short stories. If he had left fiction unfinished, he must have eventually returned to it. Only unfinished endeavours and unfulfilled commitments continue to haunt us, prompting us to resume them. The pressing question is why Ghazi sahib chose to publish stories that are 70 years old.

Over the past seven decades, Urdu fiction has experienced numerous thematic and aesthetic transformations. Does he — or his younger associates who insisted on him to publish these stories — believe that these stories possess literary significance that transcends both history and time? Do these stories resonate with readers in this postmodern, post-truth, AI-driven era? Moderately, yes.

All 10 stories in the collection delve into the theme of love through a young male narrator. This Karachi-based protagonist is a solitary adult, searching for his Sosan, an archetypal figure of womanhood. Although he encounters women, he quickly loses them. In these tales, moments of joy are rare, while hours of suffering are plentiful. In our contemporary society, the concepts of love and sexuality have undergone major shifts. So, at places the protagonist of these stories appears like an individual of an old generation.

What renders these stories valuable today is their stylistic approach. Ghazi sahib’s fictional prose is remarkably creative, engaging and captivating, allowing it to still resonate with readers. It is astonishing that he possessed such a flawless yet imaginative style even in his teenage years.

Additionally, there are several other factors that contribute to the relevance of these stories.

In the 1950s, when these stories were crafted, the Urdu literary landscape was overwhelmed by three significant movements: Progressive, Modernist and Cultural Nationalist. Each of these movements grappled with the critical issues surrounding Partition, including the resulting violent communal riots, migration, displacement, and questions of cultural and national identity.

At that time, Ghazi sahib was a teenager living in Karachi. On the surface, his stories may appear to be disconnected from these grand national issues. Yet, on a deeper level, the characters endure the pain of displacement and crises of identity as well.

These narratives are characterised by a modernist approach, as they delve into the inner turmoil of young individuals marked by romantic struggles, while largely ignoring the anxieties stemming from the class system. It is important to emphasise that the romantic struggles faced by the young protagonists bear significant psychological similarities to those induced by displacement. All 10 stories can be classified as ‘love stories’ told from the perspective of a young protagonist. Yet, in each tale, we encounter desires and dreams that remain unfulfilled, leading to feelings of angst and sorrow.

The most striking and memorable tale is the opening story of the collection, ‘Veeranay Mein Do Awazain’ [Two Voices from the Wilderness]. In this narrative, human existence is depicted as a wilderness, with the two voices representing passion and revulsion, loyalty and betrayal, acceptance and rejection.

The conflict inherent in the perception of love is central to the story. The main characters, Faruq and Abida, embody this conflict, resulting in their inevitable separation. Their longing for love only exacerbates the horror of their wilderness and sense of homelessness. Intriguingly, Faruq equates love with the concept of home, suggesting that we seek a home not only for safety but also for order, tranquility in our lives and for a space of mediation on our fundamental existential issues. Love serves as a sanctuary for our wandering spirits.

Kashif Raza, in his essay included in the book has skillfully peeled back the layers of this story. It is noteworthy that in Ghazi sahib’s stories, the young lovers based in Karachi grapple with a profound sense of internal displacement.

‘Jeena Wada Khilafi Hai’ is a story that highlights the idea, as expressed in the second line of Mahbub Khizan’s famous couplet (‘Ek mohabbat kaafi hai/ Baaqi umr izaafi hai’ [One love is enough/ The rest of life is surplus]), that we only need one love; living without it feels like a betrayal. It emphasises the harsh truth that love often leads to tragedy — a tragedy that we lose our loved ones, even betray them, but keep living in the wilderness of our beings.

Is it merely a coincidence that one of the stories is titled ‘Mera Ghar Kahaan Hai’ [Where is My Home?]. The narrator-protagonist reminisces about his beloved Nafeesa, who has married someone else, while he searches for his home, a small paradise on earth. He states, “I hate big houses; I just need a small home.” Ghazi sahib’s fictional characters struggle to find their home. The quest for home is a recurring theme throughout these stories. They often feel ‘out of place’, whether they are in cafes, at the airport, in Murree or in Lahore.

‘Ban Basi’ [Jungle Dweller] is another short story where the protagonist feels disconnected. He comes to the realisation that neither his father nor his mother truly belongs to him. He feels estranged from his parents’ home as well. Even in his own home, he experiences a sense of being ‘out of place’. He grapples with an identity crisis and feelings of estrangement, which continue to resonate with us.

The reviewer is a Lahore-based critic and short story writer.

He edits LUMS’ Urdu research journal Bunyad.

His new book Mera Daghestan-i-Jadeed is in the press

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, November 23rd, 2025

from Dawn - Home https://ift.tt/JyTnA1K

Comments

Post a Comment